Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes philosopher

Thomas Hobbes was a prominent English philosopher and political theorist of the 17th century. He is primarily known for his works on social contract theory and his creation of political philosophy, which emphasizes the importance of a strong and centralized state. Hobbes is best remembered for his famous book, Leviathan, where he argues that human beings are naturally selfish and aggressive, and therefore require an all-powerful government to maintain order and protect their basic rights. Hobbes described the state of nature, as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”.[1] By entering into ‘social contracts’ with one another, individuals recognise that only a sovereign power can secure order and stability. His ideas had immense influence in the development of modern political thought, and his work remains highly influential even today.

Modern political philosophy

Thomas Hobbes is commonly regarded as one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Active during the 17th century, his ideas had a significant impact on later political thinkers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Hobbes believed that the natural state of humanity is a constant struggle for power and resources, and that without a strong central government to keep individuals in check, society would inevitably descend into chaos and violence. This belief led him to advocate strongly for absolute monarchy, arguing that the only way to maintain order and prevent violence was through a powerful and centralized state. Hobbes' ideas were controversial during his time and remain the subject of debate among political theorists today.

The landscape

His intended audience was a tiny group of people, mostly members of the exiled Royal English Court in France and other influential people in England. What was the context for his writing? Hobbes wrote during the decline of the Christian church's superordinate power, when religious authority, rather than being a binding force, had become a significant cause of strife in Europe. What should take the place of religious brotherhood claims (and religiously oriented natural law) or localised feudal relations? The Thirty Years' War, Europe's worst battle to date, had devastated most of central Europe and dramatically decreased the German-speaking population, among other things. Few people thought 'globally' as we do today; but, in our language, the major blocs of that time appear as a divided European Christendom, with the strongest powers being the Chinese Empire, which was localised in its concerns, and the Islamic Ottoman Empire, which was somewhat at odds with Islamic Persia. For centuries, Islam, not Christian Europe, was the centre of learning, producing a universal culture that was polyethnic, multiracial, and expanded throughout vast areas of the globe.

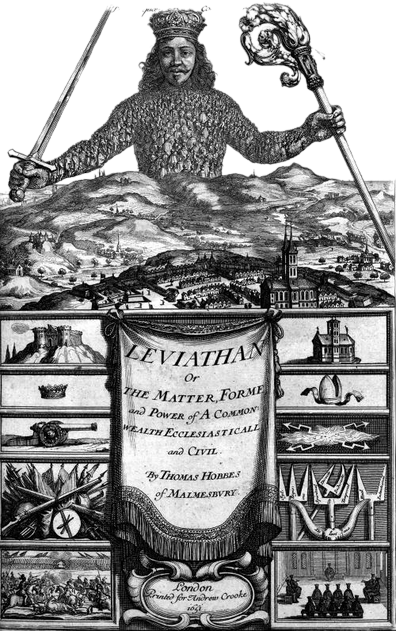

Leviathan (1651)

Hobbes is most famous for his 1651 book, Leviathan, which laid out his influential formulation of social contract theory. Hobbes' Leviathan, published following the English Civil War, tried to persuade the governing class of a new political legitimacy framework. He invented a new approach to explain governance and justify obedience. This theory of legitimacy, or explanation for why we (the "subjects") should obey it, was based on a narrative of mankind's nature and place in the universe that explained our essential issues. Hobbes argued that individuals must give up some of their natural rights and freedoms to a powerful central authority in exchange for protection and security. This concept of a social contract between rulers and citizens has been deeply influential in political thought and has helped shape modern political systems. We were supposed to perceive ourselves as participants in this story and agree that sensible people need powerful governments. His social pact justified modernity.

Notion of Law

Thomas Hobbes, the English philosopher and political theorist, is credited with postulating the first detailed notion of law based on the idea of sovereign power in his work "Leviathan". According to Hobbes, the sovereign is the ultimate authority and all laws derive from its power. This idea challenged the prevailing view that law is something posited by man, it does not flow from God’s creation. Does morality have to be present for anything to be acknowledged as law? What about judicial decisions? In his lifetime, the great common law judge Sir Mathew Hale attempted to defend the traditions of the common law against Hobbes by arguing, in part, that the common law contained accumulated wisdom, whereas the image of law as the commands of the sovereign would encourage ad hoc decisionmaking or grand political agendas. Hobbes would seem to say no: it is a matter of sanctions, of the power to enforce the positively laid down legal statement. When Bentham and others understood the law as a tool of rational rule, to be utilised by the political masters and guided by a firm ethical philosophy—utility—the force of legislative reason truly began to develop in the 19th century.

Sovereign's will

Hobbes advocates for a sovereign authority with ultimate power to deliver humanity from the "state of nature" in which existence is a "war of all on all" due to man's egoistic nature. Hobbes was the first political philosopher to base his theory on "materialist" (scientific) views of persons and the universe. This sovereign, according to Hobbes, is the ultimate authority in the state and has the power to create and enforce laws. Because the sovereign is the only legitimate source of authority, the laws they create are solely dependent on their will. This means that there is no law outside of the sovereign's command, and their word is the final say on what is right and wrong.

Positivist views

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) founded liberalism. His work transitions from the mediaeval philosophical synthesis, which saw God as the creator of life and his presence in the organisation and life flows of the world, to a more secular basis for administration. Hobbes was the father of legal positivism, yet he lived many hundred years before his time. In this way, Hobbes believed that the sovereign's authority was absolute and that the people were obligated to obey their commands or face legal consequences. It was a positivist system designed to provide stability and security during a time of social and political turmoil with the expectation that a single, strong, and authoritarian ruler could keep the peace and prevent anarchy from taking over.

Critique of Hobbes

Hobbes' thesis may be argued to imply a near absolute state. Why would someone delegate so much authority to a single body? There is a dread of assault inside the state of nature, but it is from individuals of nearly equal strength; an attack from the state, on the other hand, has enormous power. The second issue with Hobbes theory is a conceptual challenge with internal consistency. If self-protection is the reason for obedience to a sovereign, then those enforcing the rules can refuse to implement or execute a command if they believe doing so would endanger their lives, and thus Hobbes alienation theory can be seen to collapse into John Locke's agency theory.

Locke maintained that man could not give up more authority over himself than he now had. Locke argues that just handing rights to the state is sufficient. Locke's theory of the origins of political responsibility includes a social contract as well, but it entails the formation of two contracts rather than one. Men agree to join a political society in order to increase the security of life, liberty, and property that they enjoy in their natural condition. Then a political community is created, and a contract is made between this political community and the government.[2] Locke emphasises the concept of citizens' permission in his literature, and everyone having consent is defined as such.

Footnotes

[1] Hobbes, Thomas. cited in Stychin, Carl F. Legal Method text and materials, 1999, London: Sweet & Maxwell, p.2

[2] Two Treatises of Civil Government, ed., W.S. Carpenter (J.M. Dent, London, 1924 (1962 repr.)), 164-6, First published 1690 cited in Rosen, Michael, & Wolff, Jonathan, Political Thought, 1999, Oxford: OUP, p. 59

LAW BOOKS

Our Core Series books will help you understand the complexities of legal topics. Candidates for the LLB, SQE, PGDL, GDL, CILEX Qualification Framework, and University of London LLB Curriculum should take note! With our Q&A Series books providing authorised answer sets, you can easily prepare for examinations. Perfect for students looking for a thorough study assistance.

Jurisprudence Notes

The Contents

Chapter 1 - Jurisprudence

Chapter 2 - Natural Law

Chapter 3 - Legal Positivism I

Chapter 4 - Legal Positivism II

Chapter 5 - Hart’s rule of Recognition

Chapter 6 - The Hart Fuller Debate

Chapter 7 - Kelsen: Pure Theory of Law

Chapter 8 - Raz

Chapter 9 - Dworkin

Chapter 10 - Liberalism and law

Chapter 11 - Marx, Marxism and Marxist Legal theory

Chapter 12 - Feminist Legal Theories